As I stand back looking at this woman, I see an undeniably graceful, vivacious beauty. Her shoulder length, dark hair glistens as her light brown eyes sparkle with dark brown specks; there is an amazing gleam from within. Her eyelashes are to die for. With her elegant bone structure and high cheek bones, I know she is a European model. Such an even, smooth ivory skin tone, it looks almost too soft to touch, like that of a porcelain doll. I want to reach out and touch her face, but I dare not, I fear she may break. She is a tall woman, standing at five-foot eleven-inches, and I can see by looking at her structure she is athletic. Everyone else calls her by her given name, Vida, meaning life in Hebrew. I call her mom. She was born February 9, 1939, in Liverpool, England.

My mother was there for me when I was 18, a senior in high school, and was diagnosed with cervical cancer. She held my hand in comfort, and she talked me through it. She held me when the doctor told me that my chances of having children were slim to none. She cradled me as a child when we arrived home as I cried my eyes out at the thought of never being able to have children of my own, the thought of never trying to be as great as she, never giving her grandchildren. Her voice was just as soothing as that of Celtic singer Loreena McKennitt singing "Donte’s Prayer." I later came to accept the reality of no children, but not for long.

While I was in the Army getting the paper work together to be a helicopter pilot, I was told I was pregnant. I was stunned.

I stated to my doctor, “That is not possible; I am unable to have children.”

He stated, “I know, it is in your medical chart.”

“Retake the test again,” I iterated.

He stated, “I have redone the test three times.”

As I sat there stunned, realizing my dream of being a pilot was gone, but the dream of having a child was so overwhelming; I cried. My doctor told me that I would have to have what was left of my cervix meshed closed or I would lose my baby. I did not understand the process at the time, nor did it matter, I was going to have a baby. I was given a list of what I was allowed to do, and what I was forbidden to do, which was overwhelming. I could not wait to tell my husband that we are pregnant.

My husband's first remark, “We can’t have kids.”

I replied, “That’s what I told the doctor.”

On September 28, 1984, my twenty-first birthday, I gave birth to a son, weighing seven-and-a-half pounds, and he was twenty-two inches long. That was the happiest day of my life. I switched careers in an instant, from a soldier to a mother. I was so proud to have the honorable title of mother.

In 1985, my mother called me. I love the sound of her voice, and after being in this country for 25 years and becoming a United States citizen, she still had that heavy British accent. She called to tell me that she and my father found a lump, and it was cancer.

I was terrified. I was petrified. I was shaking as though I had been diagnosed with breast cancer. I was living in Germany, while she was in California. I told her I would take the next flight.

My mother said her usual saying, “Everything is already taken care of, a massive mastectomy with 24 lymph nodes removed, and they got it all. There is nothing you can do here, and you would just be in the way.”

I replied, “You already had surgery?” I asked her if she was going to have reconstructive surgery.

She replied humorously, “No! I always wanted to know what a falsie felt like!”

That is just the way she handled everything, get it over with and then tell us. I never understood my mother’s madness, her way of thinking. How many of us can say we ever understood our mothers? She went on to have chemotherapy, with the right side of her chest gone from the back side of her underarm to her left chest wall. She made it all seem easy as if it were a walk in the park. I envied her strength, her attitude. I was already married with a child of my own. I kept thinking that when I grow up I want to be just like her; I am still working on that part.

I can recall my mother calling to tell me. She and my dad were in a motorcycle accident in the mountains while doing a charity run to Las Vegas. She told it as if it were no big deal, as if it happens to her and my dad all the time, so nonchalantly. Some “twits”, as she called them, did not stay in their lane. Later, when I went to visit them in San Diego, my mother’s girlfriend, Betty, told me the whole story. As my parents were rounding a curve, heading up in the mountains, a car came into their lane. My father had two options, hitting the car and taking the chance of going over the side of the mountain, or hitting the mountain itself. Choosing the lesser of the two evils, he headed into the mountain.

My mothers’ collar-bone was broken, her arm was broken, and her hip a massive bruise. My father broke a rib, which punctured his lung. His arm was broken, and he sprained his ankle; all in an effort to keep his enormous touring bike off mom.

My mother was going through chemotherapy at the time and no one knew. She always had on a scarf and would not let the paramedics take off her helmet to work on her; she was in fear that her scarf would come off and then everyone would know. Everyone would see her baldness, and think she was weak, seeing she was not who they thought she was. She did not want their pity; she just wanted to be treated as they always have treated her.

It was December 1990 when I received the news that I had cancer, again. This time I was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. I completely fell apart. What could the doctor’s take away from me this time? The doctor would remove my thyroid, part of my parathyroid, and some lymph nodes. The doctor told me, before I went under that January morning, I would have a half inch scar and in six months no one would notice, and I would be on medication for the rest of my life. Hog wash! I awoke with a six-inch scar. I was constantly asked what happened to my neck. My humorist reply, “I was slashed, but you should see the other guy!”

I waited until I had surgery to call my mother. I guess the apple does not fall that far from the tree. When I called to tell her, she also told me she was sick again. My world came to a complete stop. This can not be happening. I wanted to scream, not for me, but for my mother. She fought for six years to beat breast cancer; it had gone to her liver. She was not a drinker. Each time she would have a sip of something she would get, as she called it, “blotchy.” My mother and I living on the opposite side of the United States, neither able to travel, talked through this every day. Our phone bills were outrageous, but it was worth every penny. The doctors gave her six months. I gave her a lifetime. In those six months, I intended to live a lifetime with my mother. I told my mother, “I am cancer free.”

There was no choice in the matter. I felt I had no other option. I could hear in my mother’s voice that she was so grateful, she was at peace. At that moment, I knew I did the right thing. I did not want her to worry about me anymore; I wanted her to be her only concern.

My father called me two weeks later on a Friday evening. I will never forget what he told me, “She is not going to make it through the weekend.”

I cringed with my response, “How was that possible? My six months were not over yet. Dad, someone lied to us; we still have five and a half months with mom.”

I slid to the living room floor, my legs unable to hold me. I sat there thinking that someone owed me that time with my mother. I did not care where the time came from; I just know I needed that time. There was so much we had left to do, to say, two weeks was nowhere near enough. A lifetime was nowhere near enough. She was to be here while her grandchildren grew up. Something was not right. He had to fix it. I begged my dad to fix it. I asked him, “What happened?” He did not know. I told him I was taking the next flight. Before I could get a flight out, she died at the age of 52.

I hated watching my six-foot six-inch tall father weighing 350 pounds emotionally and physically shrink down to the size and age of a four-year old. I hated standing by and watching his world fall completely apart after almost 30 years of marriage to the love of his life. At that moment, I forgave him for everything that happened when I was a child. I hated seeing the looks in my brother’s eyes as they tried to hold it all in to show their strength. I hated seeing the deep sorrow in my grandmother’s eyes as she lost her oldest daughter just two years after losing her husband of 53 years.

Most of all, I hated going through my mom’s things. A part of my heart went with each thing as I gave them to charity and to those who meant so much to her. The last two things I threw out would have been the ones she would have thrown out first, her wig and falsie. She hated wearing them and what they represented. However, in my mind and in my heart, holding onto them for an extra day meant she was still with us. I do have the peace of knowing she thought I was cancer free. Two weeks later I started radiation.

To this day, March 8 of every year is the worst day of the year. There is an empty feeling deep inside that does not go away. There is a feeling of something missing. I am aware of an ache, a twinge of something I can not explain nor would I, if I knew the unknown words. The pain is not as raw 27 years later, but it's still there. I miss talking with her, smelling her, listening to her soothing voice to comfort me. I miss her engulfing hugs, her boisterous laughter. I just plain miss her.

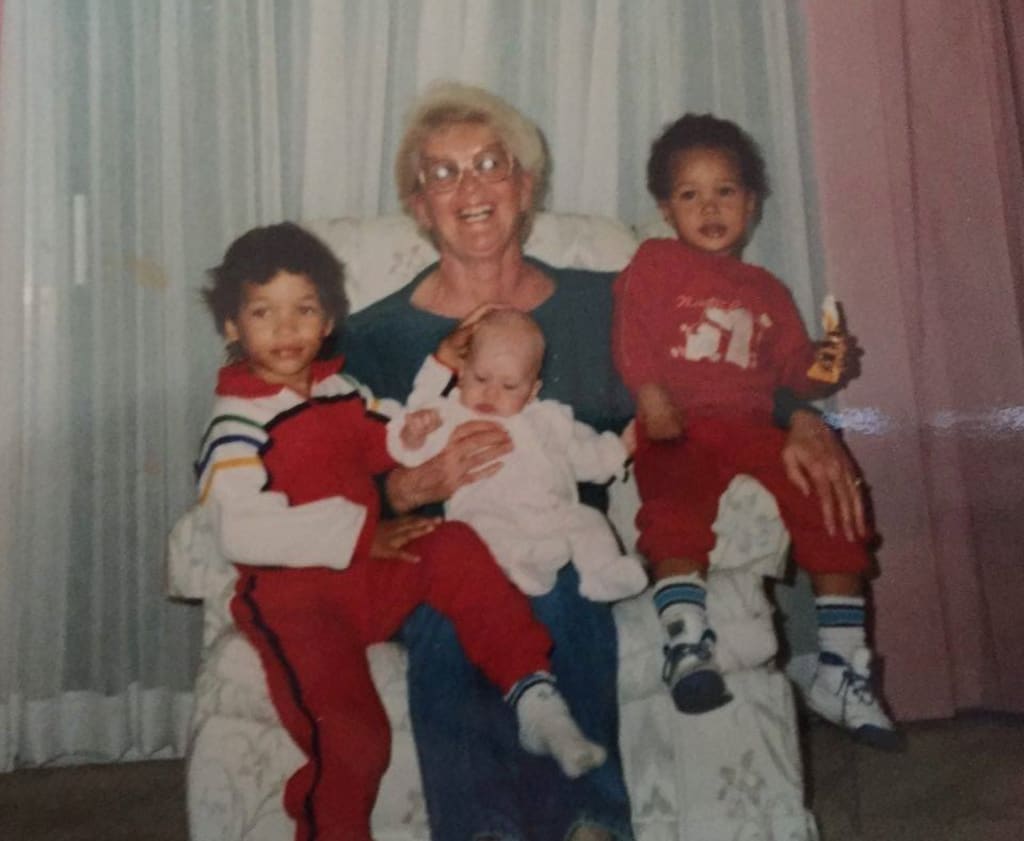

I go to the ocean every year on her birthday, my birthday, and the anniversary of her death, with a box of tissues and a bouquet of flowers. I throw in the flowers one petal at a time, knowing that somewhere, someday one petal will reach one of her ashes. I talk to her, telling her of what is going on in our lives. I tell her about her grandchildren whom she cherished. I tell her I can not wait to be a grandmother, too bad the boys are nowhere near ready. I leave with an empty tissue box, petal stained fingers, telling her that I love her and miss her so much. I leave her knowing my lying to her all those years ago gave her peace; I can live with that. You see, she was not just my mother; she was my strength, my guide, and my friend.

About the Creator

sandra gunderson

I was born and raised in Wisconsin. My greatest joys are my two sons and my three grandchildren, which I cherish. I am prior military, I attend college full time and work full time for the Department of Defense.

Happy reading,

Sandra

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.